My mission is one reason I have decided that I can survive anything for a year and a half.

My memory of that time is a little like a badly copied VHS tape—blurry images, missing chunks, and a cheerful soundtrack dubbed loudly over whatever I was actually feeling. When I look through the few photos I still have, I’m always smiling. I look like I’m having a great time. Like I’m thriving. Like I’m spiritually glowing.

The pictures were lying.

Or maybe I was.

In reality, I was asking my Mission President if I could go home at every possible opportunity.

Of course, I was always denied.

I never let on in my letters.

It wasn’t all miserable. There were bright spots—real ones. I met a few girls, fellow missionaries, who I genuinely loved. I ate some delicious food. I met a lot of interesting, kind people.

But I wasn’t there to make friends. I was there to “save souls.” And I wasn’t good at the job. Not bad—just… ineffective.

One afternoon while we were tracting—door-to-door proselytizing—a man opened the door, listened politely for about three seconds, and said, “No thanks. I already know about Joe Smith.”

Joe.

I felt it immediately. Not emotionally—physically. A sharp, offended jolt. My jaw tightened. My stomach clenched. Which was ridiculous. I knew it was ridiculous in real time. Why did that bother me?

He hadn’t insulted me, or my religion. He wasn’t rude, or angry. He just… shortened a name. In Mormonism, we don’t shorten the names of prophets. You don’t nickname holy men.

And standing there on that porch, it occurred to me—dimly, uncomfortably—that Joseph Smith wasn’t just a historical figure to me. He was a protected symbol. “Joseph” was reverent. “Joe” was not.

That reaction wasn’t faith.

It was conditioning.

Once you notice the strings, it’s hard to pull them convincingly.

I didn’t try very hard to push people toward baptism. I did manage to get one guy baptized—I’m pretty sure he did it because he thought one of the sister missionaries would date him if he did. He didn’t know about missionary standards.

There was another woman we taught who had been getting the lessons for years. Missionaries cycled through her, lesson after lesson, but she could never get baptized because her husband wouldn’t give permission (meaning he had to formally approve it with church leadership)—apparently God needed a man to sign off on her salvation. So eventually, she’d just start the lessons over again.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, my mother had tried to go to the temple—and couldn’t, because Dad wouldn’t sign off on it.

I can’t entirely fault him. The sacred underwear is tragic, and letting her promise to give the church everything is a big ask.

But the requirement itself—the idea that a woman’s access to God depends on a man’s approval—

yeah.

Fuck the church for that.

I’d learned Spanish pretty decently, but this was California. I never had to become fluent. I could deliver the lessons, but I was never great at conversation and bonding. Speaking Spanish made me nervous. It made my lip sweat.

My most successful contribution to the work was probably teaching my final companion how to ride a bike.

In a skirt.

This is where the mission briefly became a slapstick film.

Allow me to insert a story here: riding a bike in a skirt is unpleasant. Riding a bike in a dress, with a massive pad during your period, is worse.

Mom didn’t use tampons. The one time I asked her about them, she made her feelings very clear. So I didn’t either.

It wasn’t working out.

One of my companions had to explain tampons to me. She sat outside the bathroom door and talked me through it. Poor Hermana Casdorph. That is not what she signed up for.

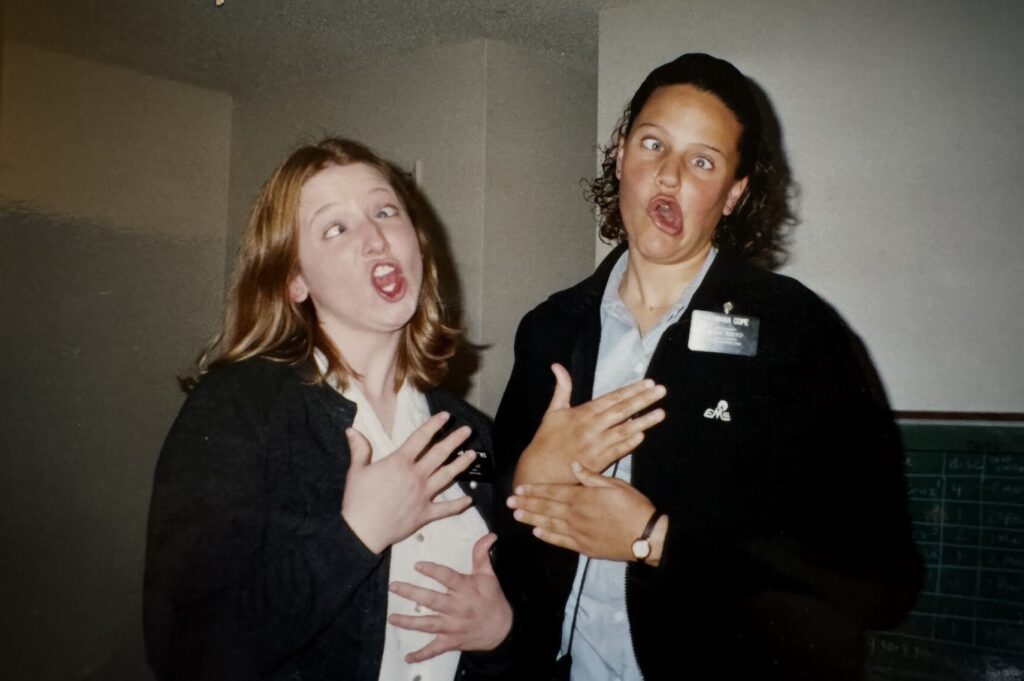

Let’s see who I can remember. I am absolutely certain to forget people.

My first companion was Hermana Rodriguez. She was what they call “trunky”—ready to go home. I resented her for it. Her reluctance to teach me. And the fact that she was almost done, while I was just beginning.

Hermana Cope was allergic to wheat. Her stomach would distend alarmingly when she ate it—but she always did when offered, so as not to be rude.

Sister Gallup taught me how to belch properly. A deep, resonant, window-rattling belch that still horrifies and delights my brothers. (My most enduring talent from the mission.)

Hermana Moody and I choreographed dances to the ice cream truck music—the “Do Your Ears Hang Low” version and the “Hands in Their Pockets” version. Whenever we heard the tune, we’d break into motion. The vendor would yell as he passed: Hello, happy sisters!

We also raced to crunchy leaves to see who got to step on them.

She sadly passed away last year from cancer.

I don’t remember many of the Elders. There was Elder Workman, who seemed nice and later turned out to be a super right-wing nutcase.

And Elder Billings, who introduced himself as one of my brother Alan’s friends from school. He was also from Orem. Tall. Quiet. Serious. Intimidating. He always made a point to talk to me when we crossed paths.

We usually lived in apartments, but in one city we lived with members. Inactive members. It was strange the church allowed it.

The wife wore only a large T-shirt to bed. Except it wasn’t large enough. I saw her pubic hair on many occasions. It was horrifying.

Some things cannot be unseen.

This was one of them.

Mom kept writing faithfully. She sent care packages—cake mix and candles for my birthday, shoes when mine wore out. I didn’t appreciate then that she was paying for me to be on my mission. She was still working at the beauty shop, washing hair with eczema-riddled hands.

I kept writing to Reed, too. We swapped mission stories. He sent me roses once, from England, after a bad day—calling me on the phone just before they were delivered.

That broke some mission rules.

We weren’t allowed to listen to worldly music. I only had so much contraband from Jason, so I developed a fondness for Disney soundtracks and Christian rock.

I belted “Be a Man” from Mulan, complete with choreographed movements I made all my companions learn. Only hand gestures. To accommodate both car and bike dancing.

And then there was 9/11.

The world cracked in half while we had almost no access to information.

We were gathered into a church building and told the broad strokes. We were warned to avoid violence. And specifically told to avoid “brown neighborhoods.” (That was the phrase used. Not mine.)

Which was awkward.

Because we lived in one.

We had one appointment that day, so we went. The family wasn’t interested in salvation. They were glued to the TV.

Missionaries weren’t allowed to watch television, but no one enforced that rule that morning.

We sat with them and watched the horror unfold. Quiet. Helpless. Very, very small.

Where was our Messiah now?

Eventually, they asked us to leave. So we wandered the streets in shock. People drove past and yelled at us to go home. I agreed. I just didn’t know if we were allowed to.

It was a strange, hollow day.

On other days, we got fed.

A lot.

People were endlessly entertained by two gringa girls speaking Spanish with varying confidence. One of them with gigantic chichis.

“No, I don’t want to convert, mija. But here—have a taco. Take this chicken. Eat this avocado right now.”

I fell in love with mole. Tamales. Horchata. Posole. Burritos the size of my forearm stuffed with carne asada.

I only got twenty-five dollars a week for personal expenses. I snagged a lot of nylons biking, so replacing them ate most of my money. So when someone handed me food, I ate it. Except for Menudo, I could never stomach…stomach. I ate what was offered, even when I wasn’t hungry.

I was only in San Jose proper for a few months. Then I was transferred to smaller agricultural towns south of the city—Campbell, Greenfield, King City, Salinas, Hollister—where the Mexican farmworkers were.

When I got home and saw people wearing “Hollister, CA” shirts, I was deeply confused.

“HEY! I lived there! On C Street!”

They looked at me like I was an idiot.

I do not understand why anyone would name a clothing line after that town.

It smelled like celery and manure.

Near the end of my sentence, the Mission President—apparently alarmed by our low conversion numbers—brought in a consultant.

A consultant. Nothing screams divine truth like middle management.

We were coached to knock on doors and offer to bless homes, and share a message about the name of the Virgin Mary. That would get us inside.

Once everyone knelt to pray, we were supposed to immediately launch into Joseph Smith.

It was manipulative.

Brazenly so.

I felt my stomach twist. This wasn’t faith anymore. It was strategy. A moral line had been crossed somewhere far behind us—and I was just noticing.

That was my breaking point.

Thankfully, it came near the end.

I finished my eighteen months.

My parents drove out to get me.

And just like that—

I was free.

Leave a Reply