On the scheduled day, my parents drove me to Provo, stoic and silent. We sat through a short program together—an inspirational video about how we were going to save the world, a song, a prayer—and then came the instructions: missionaries out the back, parents out the front.

I gave my mom and dad light, careful hugs and started walking away. At the door, I turned back. They were both red-faced and sobbing.

A hand appeared and firmly pushed me through the exit.

Things have changed over the years, but back then the LDS Missionary Training Center—the MTC—was a tightly controlled compound in Provo, Utah, where young Mormons from all over the world gathered to prepare for full-time missions.

Think boot camp, but with flowerbeds. And significantly less swearing.

Boys usually entered at nineteen. Girls at twenty-one. The logic behind the age difference was simple: those were prime marriage years for women. But if that plan failed—if no suitable husband appeared on schedule—you could still redeem yourself by going out and recruiting future tithe payers.

It was comforting to know there was a backup plan.

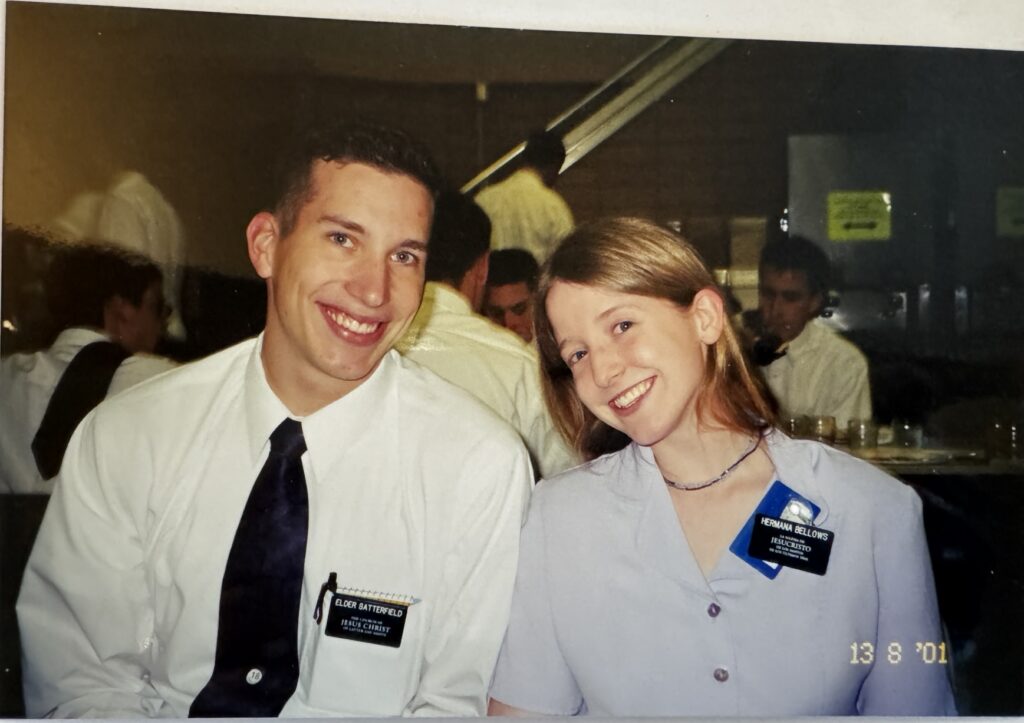

At the MTC, they drilled us in gospel doctrine, taught us how to deliver the church’s message with confidence and sincerity, and—in my case—how to speak a new language in six weeks. This was also where the missionary rules stopped being theoretical and became your entire personality. You put on a dress, clipped on your name tag, and were assigned a companion, to whom you were now spiritually, emotionally, and logistically welded.

You were no longer an individual.

You were a duo.

A brand.

Our days were packed: classes, meals, exercise, personal study, laundry, devotionals—every minute accounted for. Spontaneity wasn’t discouraged; it was aggressively rescheduled.

Mail pickup was sacred. You were given a very small, very specific window to retrieve it, and it was completely non-negotiable. So if your mother sent you a care package of hot sandwiches from your favorite deli and the delivery notice arrived after your scheduled pickup time on Friday, you simply didn’t get the sandwiches until Monday.

At which point they were moldy.

Ask me how I know.

Officially, the MTC was a transformative experience meant to build spiritual strength and practical skills—preparing missionaries for the rigors of the field.

Unofficially, it was a master class in indoctrination, salesmanship, and performing cheerful obedience on cue.

On my first day, I met my companion—a Canadian girl heading to South America. We unpacked our suitcases and our feelings, having just been exiled from our families for the next eighteen months. She climbed into bed and fell asleep almost immediately.

I sat on the edge of my bed, still fully dressed, staring at my shoes, wondering what on earth I was doing there.

I briefly considered making a run for it. The gates were locked, so I’d have to climb the fence, which would be tricky—but not impossible. And once I was out, I wouldn’t have to walk far to find a pay phone. I could call home collect.

I was still trying to process how profoundly disappointing the temple had been. I hadn’t signed up for a religion whose path to heaven involved hokey costumes and secret handshakes.

Seriously?

That was the grand cosmic truth?

It all felt like a farce—but it was a farce I was now trapped in by social obligation. Friends. Family. Neighbors. Former coworkers. Everyone knew I was on a mission. If I left, there would be rumors. Speculation. Quiet judgment.

I would be cast out of my society.

No. I didn’t want that.

So, I changed into my pajamas, cried for a while, and eventually fell asleep.

A few days later, I learned that Cami’s mom worked in the MTC front office. I told my companion I wanted to say hello—and while we were chatting, I may have asked, semi-jokingly, if I could use the phone to call my dad to come get me.

I don’t know who ratted me out. Cami’s mom. My companion. Possibly the Spirit.

I was summoned to see the bishop over our group of missionaries. I told him exactly what was going on. I’d changed my mind. I wanted out. Immediately. My dad was only twenty minutes away. I could be packed and gone before he finished his Diet Coke.

The bishop—whose name I do not remember, and who almost certainly did not remember mine—expressed disappointment in my weakness. He suggested this was Satan trying to lure me away from a sacred calling. He assured me that deep down, I wanted to serve the Lord and the fine people of (checks notes) San Jose.

He believed he knew me better than I knew myself.

He had a penis, and therefore, revelation.

When I didn’t immediately recant, I was escorted to an empty classroom, handed my scriptures, and told to pray until my desire to serve the Lord returned. I don’t know if the door was actually locked, but it didn’t matter.

I knew I wasn’t leaving.

So, I sat. Hours passed. I cried. I tried to think. I flipped through my scriptures, hoping God might highlight something helpful. Let’s see—he begat him who begat that guy. Nope. “And let mine handmaid, Emma Smith, receive all those that have been given unto my servant Joseph…”

That felt like something I should look into later.

Not helpful now.

What was helpful was the rumbling in my stomach.

Years of anorexia had left me with hypoglycemia. I’d already missed lunch. If I skipped dinner, I was going to get very sick. And the cafeteria ran on a schedule.

There was no forgiveness here.

If I wanted to eat, I had to surrender—at least temporarily. I could make another plan later.

I knocked on the door. One of my teachers opened it. I told him I’d go on the mission.

They patted me on the head—figuratively, but honestly not by much—and dismissed me for dinner.

My determination to escape did not survive supper.

My family sent me regular letters. I collected them greedily from the mailroom guard and carried them off like contraband—much the way I would have handled those sandwiches, had they survived. Sigh.

Jason wrote to tell me he was getting married. They’d dated for forever and somehow waited until I was safely sequestered in religious custody to finally tie the knot.

Punk.

But he also started sending me CDs he’d burned full of borderline-approved music, so I didn’t have to spend the rest of my days marinating in the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. For this, he was forgiven. Somewhat.

Alan sent me personalized stationery he’d made on beautiful paper, because of course he did. So nice.

I was reading one of his letters in a large hall that was slowly filling up for a devotional. He described walking into a bank wearing his stylish wireless sunglasses when—due to what he suspected was a sudden change in air temperature—they exploded.

A shard of tinted shrapnel bounced off his eye.

He yelled, “FUCK!”

And found himself in a quiet room full of bankers, all deeply confused as to why a strange man with exciting eyewear had entered their establishment.

As I read this, I let out a loud “HA!”

In a very quiet room.

Full of missionaries.

Different explosions.

Same crime.

Only one of us was allowed to slowly back out of the room and go home.

Jason and Alan have birthdays a few days—and years—apart, so I went to the little campus bookstore and bought birthday cards for both of them. I addressed them. Stamped them. And sent them.

A month early.

A mistake I am still mocked for to this day.

Hey—I was in the middle of being brainwashed. They were lucky I remembered they existed.

Of course Mom wrote to me. Weekly. Religiously. She always included photos so I wouldn’t miss important milestones—like Jason’s wedding. Or his new house. Dad would occasionally sign his name at the bottom of her letters, too.

Such a dad move.

Eventually, I finished my training. I learned Spanish surprisingly well, though with a strange Castilian accent that absolutely no one in California would ever appreciate. I memorized the standardized discussions—six lessons, scripted and timed, with baptism as the stated goal at the end.

Sales, but for Jesus.

I packed all my belongings into a single piece of luggage and said goodbye to my first companion, who was headed somewhere else. I was sent to the airport.

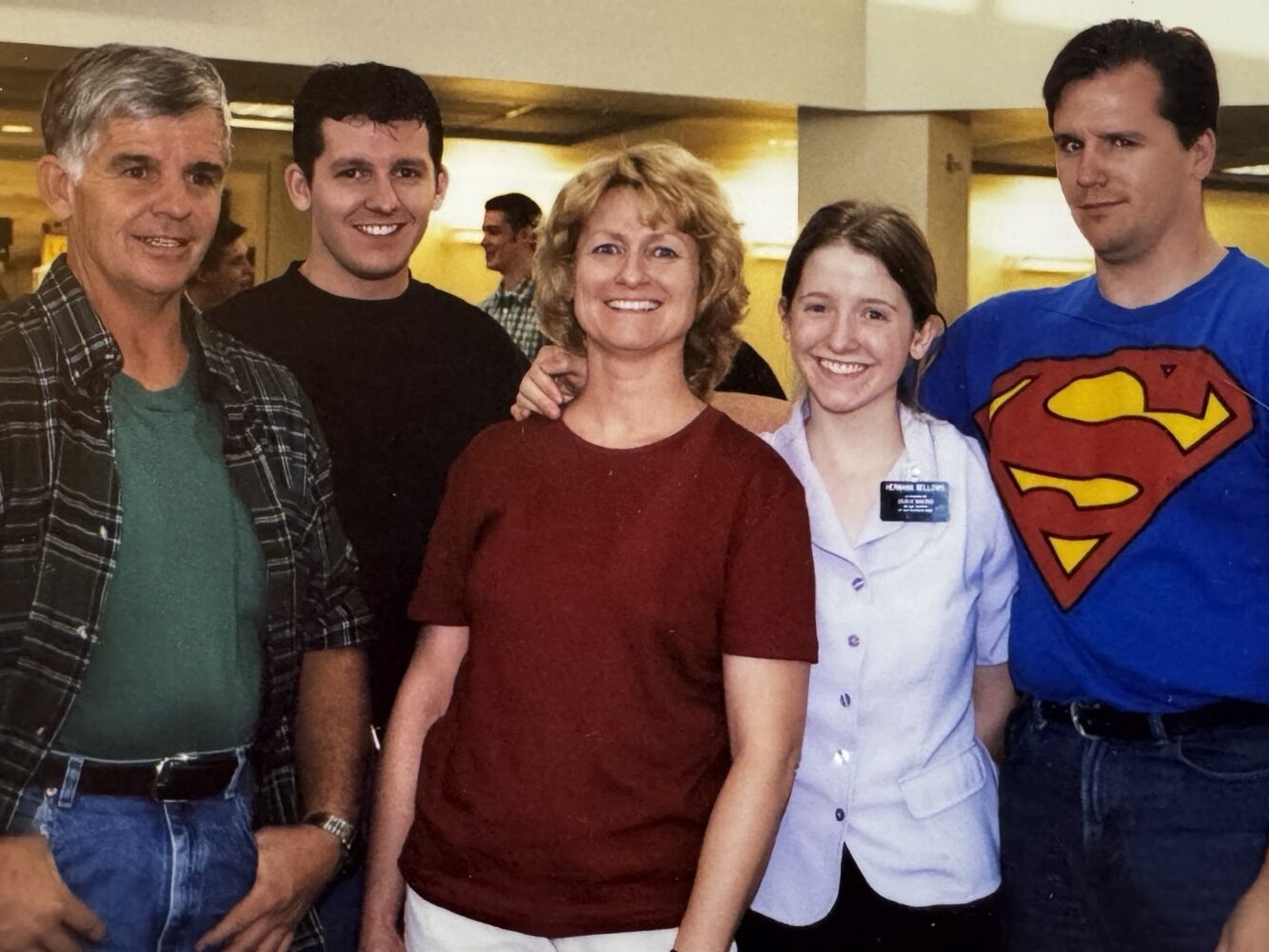

My family came to see me off—back when people without tickets could still walk you to the gate. It was painfully awkward. I was genuinely happy to see them.

I just would have preferred to leave with them.

Instead, I got on the plane. Not because I wanted to—but because that same invisible pressure was still there. The fear of what would happen if I didn’t. The looks. The whispers. The disappointment.

And through all of it, one thought kept circling, quiet but persistent:

I was no longer sure I wanted to baptize anyone into this weird-ass religion.

Leave a Reply