I did, in fact, leave my mission early—but only by one day.

My parents had driven to San Jose to pick me up, but instead of going to the hotel they’d booked, Dad drove straight to the mission president’s house, where I was supposed to spend my last night.

He parked the van out front, turned it off, and just sat there.

So after a few minutes—realizing Dad was not going anywhere without me—Mom got out, walked up to the door, and knocked.

I was inside, halfway through dinner, when I thought I heard our van pull up outside. Then there was a knock, and someone said, a little uncertainly,

“Diana… someone is here to see you?”

I jumped up from the table and ran out the door and attacked my parents with bear hugs.

Now you may be thinking: What? She heard a van from inside a house and just knew it was her parents?

Fair. That does sound unlikely.

But this wasn’t just a van. It was a member of the family.

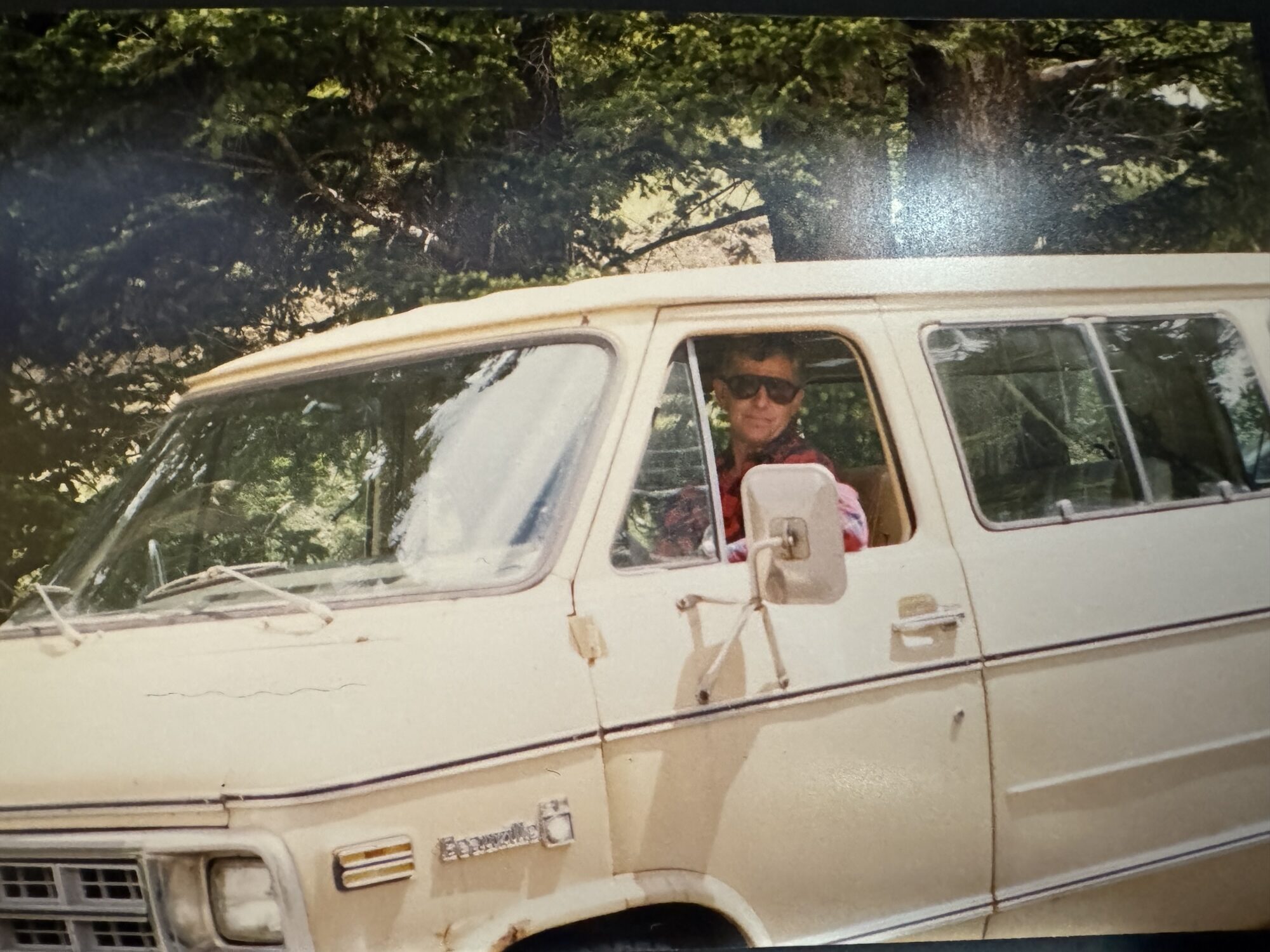

It was a 1980 Chevy twelve-passenger van—tan, boxy, unapologetic—that my dad acquired when it was only a couple of years old. I had never known life without it.

The previous owner had been in a collision. The van came into the shop battered and wounded, and Dad saw potential. He rebuilt the entire front end himself. Never bothered painting it. Cosmetics were not the point.

It was a beast.

And it sounded like one.

The engine sat high, under a big molded cover inside the passenger compartment—easy to access, impossible to ignore. When it started, the whole van announced itself. Conversation became optional. Shouting was common. Silence was rare.

That sound was unmistakable.

This van was built for road trips. Each kid had their own bench, like assigned territories in a small moving country. Jason claimed the back with his books. Alan took the middle with his headphones. I sat up front next to the cooler and the snacks, which made me very powerful.

It was my job to distribute refreshments as needed.

This authority was occasionally abused.

Mom sat in the passenger seat. Dad drove.

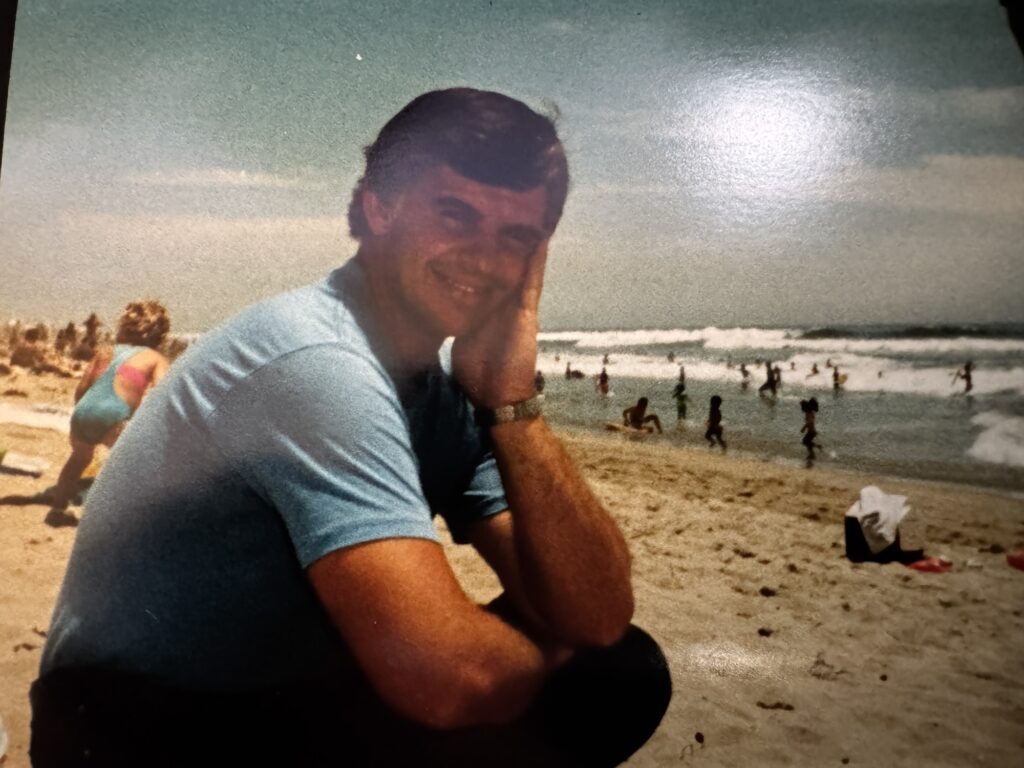

And Dad could drive.

Endlessly.

He was a robot.

He didn’t get tired. He didn’t need frequent stops. He drove like someone who had decided long ago that the road was not an obstacle—just a thing to be conquered. We drove through nights, through deserts, through holidays, through states that blurred together.

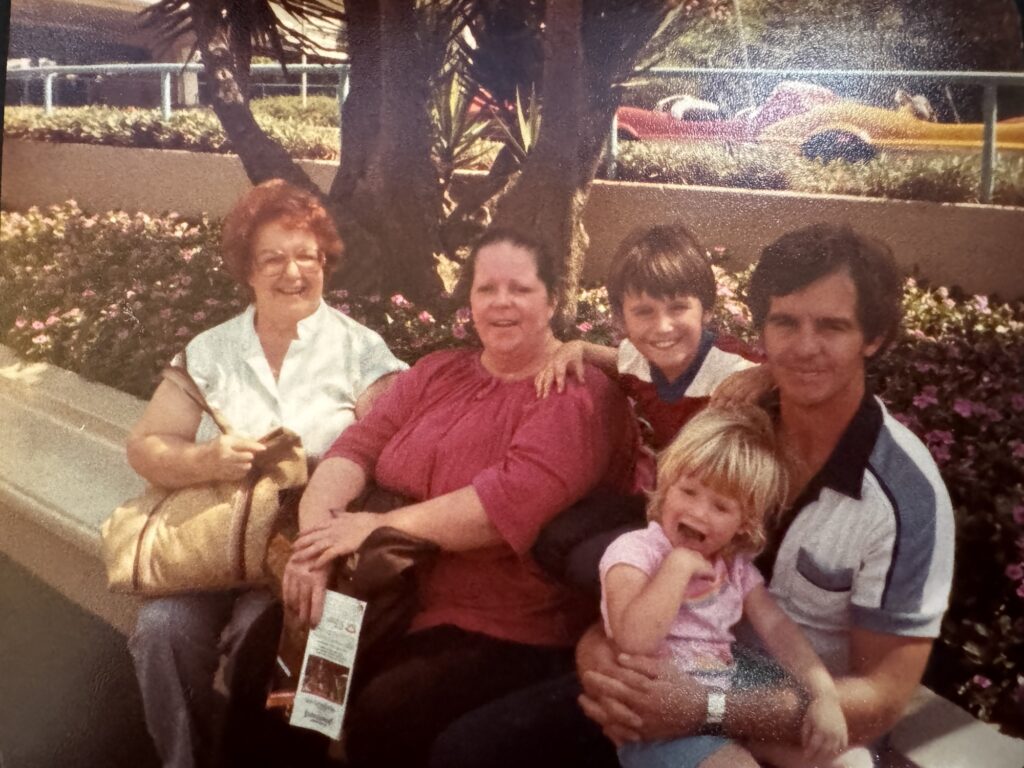

The first road trip I remember included Grandma Leona and Aunt Norma and ended at Disneyland. I was LITTLE. And devastated that I was not tall enough to ride Space Mountain. I harassed my poor parents for years afterward, asking constantly if I was tall enough yet.

Dad loved Disneyland. He drove us the 650 miles there once or twice a year throughout my childhood. He lit up on roller coasters, laughing at tight corners and sudden drops. I honestly think he would have kept going even if the rest of us had opted out.

We spent a couple of Thanksgivings on the road getting there. Denny’s Thanksgiving Special—deli-sliced turkey and canned cranberry sauce—still lives vividly in my memory.

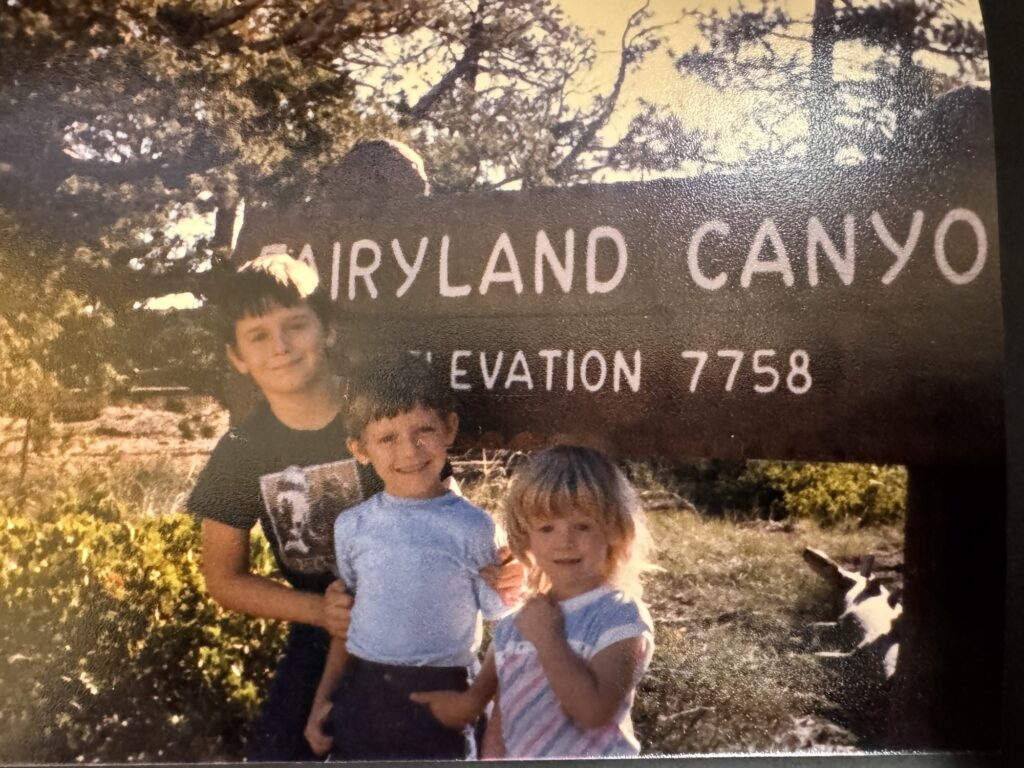

Of course, we drove other places too.

San Diego. Montana.

All the big state and national parks—Zion, Bryce, Arches, Yellowstone. Several times.

We drove in every kind of weather: sun, rain, snow. Only after the fact would Dad casually mention he’d been a little nervous about road conditions.

Like the time Mormon crickets covered the highway, their bodies slicking the pavement. He thought he might lose control.

Or the snowstorms where cars slid off the road left and right, while Dad powered through on sheer will and heroic levels of butt-clenching.

One trip, in excessive heat, the air-conditioning motor seized and we threw a belt just outside of Vegas. The van was abandoned temporarily while we rented a much smaller vehicle that had working air conditioning but none of the soul. We retrieved the van on the way back and left before dawn to outrun the heat.

One year we took our cousin—who we only ever called by his last name, Johnson—to Disneyland. He was Jason’s age, a big guy, and they were close friends. On the last day we went to the beach and swam for hours. As we trudged back to the van, a seagull dropped a giant green poop down my back and into my hair.

Everyone else found this hilarious.

I did not.

After rinsing off, we climbed into the van still wearing our swimsuits under our clothes and started the drive home. We were sunburned—badly. And full of sand that had worked its way into every crevice. EVERY crevice. And rubbed us raw.

That night, in a hotel outside Vegas, lying in bed like boiled lobsters, Johnson shared his trauma from the day: while swimming, the tide had tugged at his trunks and nearly carried them away. He’d managed to catch them with his toes and shimmy back into them before anyone noticed his nudity.

We laughed hysterically—exhausted, in pain, and deeply grateful for his dexterous toes.

Dad also drove to a car show slash swap meet in Pomona, California, once or twice a year. He’d take friends to buy parts for old muscle cars or haul their restored cars on trailers to sell. When I was sixteen, I convinced him to take me along.

This was a guys’ trip I absolutely invited myself on.

It was HOT. Over a hundred degrees. I followed Dad through endless aisles of car parts while he searched for the proper MOPAR. I tried to be a good sport while slowly melting on blacktop. Dad would pour cold water over my head when I wilted, and I’d rally just enough to keep going.

That night at the hotel, two of the guys went off to drink and gamble. Dad and I went to the pool. Clair—Dad’s big, bearded, beer-bellied best friend—lamented that he hadn’t brought swim trunks. I jokingly offered him my shorts.

He accepted.

Out he came in my purple, plaid, drawstring shorts and cannonballed into the pool, thrilled. When he offered to give them back later, that was a hard no. He could keep them.

Later that year, I borrowed the van to drive a group of kids to a Sadie Hawkins dance. I don’t know why—being a fairly new driver—I thought I could handle that beast. A few days beforehand, I took it to work as a test run. Straightaways were fine. Braking took planning. Turning and parking were nightmares.

During my shift at Albertson’s, while collecting carts, I heard the sharp mew of a kitten. I found a tiny white cotton ball of a kitten in a shoebox outside a locked pet store. In single-digit weather.

I went full crazy cat lady.

I couldn’t leave her. But I couldn’t keep her at work. The manager let me run home to drop her off. This involved driving a gigantic van while holding a tiny kitten—both making an unreasonable amount of noise—and then convincing my mother to keep her while I went back to work (I didn’t mean to permanently keep her, but we did).

It took twenty minutes to park the van.

There was a lot of time spent in that vehicle. A lot of rhyming games. Jack Handy jokes that sent Mom into tearful, hypersonic laughter. A lot of family mythology.

So when I say I heard the van from inside the mission president’s house—I heard the van.

I knew it.

My mission president and his wife were all aflutter. There was supposed to be an event: tearful testimonies, final interviews, a last blessing. They asked if I really wanted to miss that.

I was already carrying my bag to the van.

SEE YA, SUCKERS.

Leave a Reply