The LDS Church has a very clear stance on homosexuality: don’t be it.

Marriage, they taught, was ordained of God—but only the kind involving one man, one woman, and a very specific instruction manual. Anything else wasn’t just discouraged; it was framed as a threat. To families. To children. To society. To God’s entire organizational chart.

Which was rich, considering the Church’s own relationship with marriage has always been…flexible.

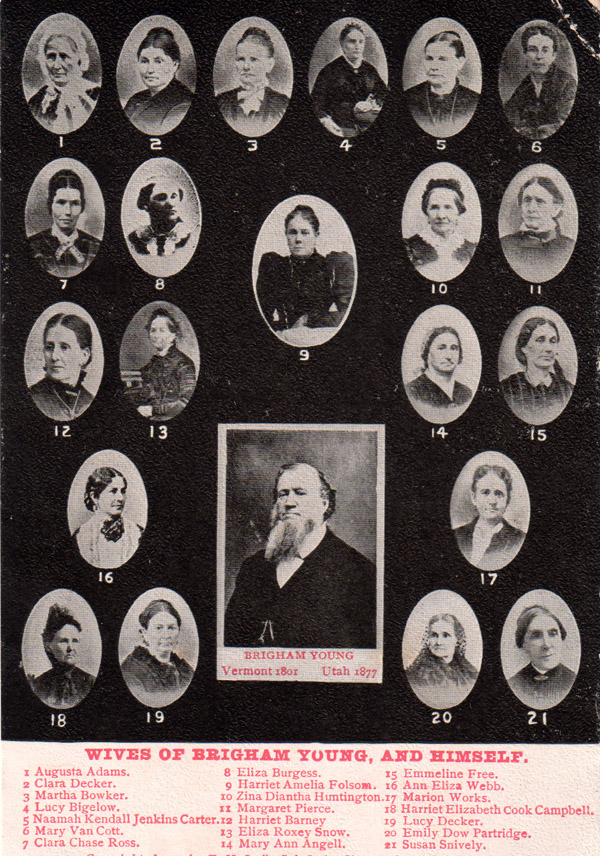

Polygamy wasn’t some anti-Mormon rumor. It was doctrine. Scripture. Commanded by God. Practiced openly—until the U.S. government made it clear Utah would never become a state unless the Church knocked it off. So, they did. Publicly. On paper.

But the revelation allowing plural marriage is still in the scriptures. It’s never been disavowed—just postponed.

In fact, Mormons are taught that polygamy isn’t gone, it’s waiting. In the Celestial Kingdom, the highest level of heaven, faithful men become gods. And gods, apparently, need multiple wives. Those wives help produce spirit children who go on to populate his very own planet.

So the eternal plan is one man, many women, infinite spirit babies, and a whole universe of heavenly bureaucracy—but two women in love, or two men building a life together here on Earth? That’s where the Church drew the moral line.

Same-sex relationships weren’t treated as relationships at all. They were called a “lifestyle.” A temptation. A problem to be managed. Something to be controlled, suppressed, or—if necessary—married away. Yes, the Church actually counseled gay men to marry women. With results so predictable they could’ve been included in the lesson manual under What Could Possibly Go Wrong.

Then, in 2008, the Church decided disapproval wasn’t enough.

They wanted legislation.

Prop 8 was a California ballot initiative designed to ban same-sex marriage by amending the state constitution. And the Mormon Church didn’t just support it—they mobilized. Members were asked to donate time and money. Bishops read letters from the pulpit. This wasn’t a suggestion. It was a call to arms, wrapped in scripture.

The message was blunt: marriage between a man and a woman was ordained of God, families were central to His plan, and children were entitled to be born only within that structure. Therefore, members were instructed to do “all they could” to make sure marriage was legally defined—by force of law—as heterosexual or nothing at all.

This wasn’t framed as discrimination.

It was framed as protection.

Of marriage.

Of children.

Of religious freedom.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks warned that this was bigger than tolerance—that society was under pressure to accept what he called “what is not normal,” and that those who disagreed were unfairly labeled bigots or homophobic. He suggested that allowing gay people equal rights would eventually lead to pastors being imprisoned for preaching against them.

In other words: if gay people got married, Christians were the real victims.

The Church insisted they loved gay people, of course. They just didn’t want to accidentally endorse their behavior—which raised some logistical questions. Like whether a gay child should be allowed to bring their partner home for the holidays. Or whether their presence might endanger other children in the house. Or whether acknowledging their relationship in public might imply approval—something to be avoided at all costs.

The recommended solution, in many cases, was polite exile.

Come, but don’t stay.

Visit, but don’t sleep over.

Exist, but quietly.

And never, ever expect us to introduce you as family.

We were also taught that homosexual feelings were controllable—no different, really, than a craving for alcohol or a tendency toward anger. Feelings became sin when indulged. Love became dangerous when expressed. And identity was something you were expected to wrestle into submission for the rest of your life.

Later, the Church announced a policy stating that children of gay parents couldn’t be baptized unless they formally denounced their parents’ marriage. That policy would eventually be reversed—but only after public outrage and real harm had already been done.

After my close encounter of the vaginal kind, I knew for sure I was never going to be needing a gay marriage. So, none of this insulted me personally. This wasn’t about my rights. I wasn’t wounded. I wasn’t defensive.

I just had this radical condition called empathy.

You know—caring about other people.

Kind of like that Jesus guy.

Not the death-metal neck-tattoo Jesus, Troy.

The Jesus guy from the Bible.

And this was the Church I belonged to.

This hypocritical, hate-filled, ass-backwards shit show.

If only on paper.

And that was too much.

I didn’t want to be associated with them anymore.

I didn’t want to be another “inactive” member artificially inflating their membership numbers.

So, I did what any modern apostate would do—I googled how to formally resign from the LDS Church. Turns out, it’s very simple. You write a letter. You mail it to the Church Office Building in Salt Lake City. Just snail mail and eternal consequences.

I wrote the letter.

And I mailed it.

Not long after, I received a response. Along with several pamphlets. The tone was polite, firm, and deeply concerned about my afterlife logistics. They explained that if I followed through with this decision, my blessings would be revoked. My access would be denied. My secret handshakes and code words would no longer work. Heaven would remain locked.

I would be a heathen.

YES.

For fuck’s sake—YES.

Please revoke my “blessings.”

Please deactivate my celestial rewards program.

Please remove my name.

The letter also informed me that my local church leaders would be contacting me to confirm my choice. Which felt unnecessary, because I had literally written a letter saying, Please remove my name.

But fine. Redundancy is big in business. And let’s be honest—the Mormon Church is a business. It owns a mall. It has an investment portfolio that could buy small countries. And it does all of this tax-free. For Jesus.

It didn’t take long.

One day I was home cleaning when I heard a knock at the kitchen door. I lived on a corner lot, so that door got a lot of traffic. Standing there were two middle-aged white men, both radiating the unmistakable energy of people who desperately wished to be anywhere else.

They introduced themselves as the bishop and the first counselor.

I was polite. Friendly. I invited them in. We stood in my kitchen and talked for maybe two minutes. They asked if I was sure. They needed verbal confirmation that I wanted my name removed from the records of the Church.

I laughed and said yes.

Then—someone started pounding on the front door.

Not knocking.

Pounding.

Loud. Aggressive. Urgent.

Normally, I would’ve answered it. But we were in the middle of a conversation, and I believed in manners. So, I ignored it.

The pounding continued.

The men looked at each other. Panicked. Like hostages who’d just heard a rescue helicopter.

They suddenly said they had everything they needed, apologized for the circumstances under which we’d met, and hurried toward the door. They let themselves out quickly—efficiently—like men executing a prearranged escape plan.

I walked to the living room door, already annoyed. I yanked it open, fully prepared to confront the rude lunatic who thought this was an appropriate way to announce themselves.

And there they were.

The entire Relief Society Presidency.

Eyes wide.

Frozen.

Horrified.

What a coincidence.

No one from the neighborhood had ever visited me since I moved in. Not to introduce themselves. Not for trick-or-treating. Not to shovel snow. But today—today they had all found the time.

They said they had a birthday present for me.

It was nowhere near my birthday.

It was painfully obvious they’d coordinated their visits so the men could escape once the women arrived. Because obviously I was some kind of violent, cannibalistic witch and they needed a clean exit strategy.

Pathetic.

I laughed. I thanked them for stopping by. And I suggested—politely—that maybe next time they could knock a little less aggressively.

They gave me a look that said there would never be a next time.

A few weeks later, I received another letter.

It confirmed that I was no longer a Mormon.

Even on paper.

I kind of wish there’d been a ridiculous ceremony to go with it. Something official. Like they stand you under an industrial dryer, you say “Oh God, hear the words of my mouth” three times backwards, and when the buzzer goes off, you get a high five and you’re free.

Oh well.

I’d just have to live with a clear conscience—finally unattached.

Leave a Reply