I moved back home with Mom and Dad.

I kept swing dancing as often as my schedule allowed—usually once or twice a week. Sometimes I’d even make the forty-minute drive up to Salt Lake to dance with the swing club at the U, because apparently gasoline and sleep were optional when jitterbugging was involved.

I also got a job, thanks to my Aunt Norma, at a beauty supply store called Sally’s. Technically, I was supposed to have a beauty license to work there. But since I had basically been raised in a beauty shop, I knew more than enough to fake it convincingly, and they waived the requirement. Turns out confidence and knowing the difference between developer strengths gets you very far in life.

It was a good job for me. They were closed on Sundays, so I didn’t have to negotiate keeping the Sabbath Day holy. And it let me indulge my obsessive need for order—stocking and facing shelves, changing sales tags monthly, and doing the occasional reset, complete with a deep clean that said, this aisle has been judged and found wanting.

I also got to feed my competitive streak, since we tracked how many impulse items we could sell at the counter.

What I didn’t realize was that the competition only benefited the manager. The Sally’s with the best numbers got their manager an all-expenses-paid trip to Cancun.

So while I was hustling deep conditioner and cuticle oil like my salvation depended on it, Deb was packing her swimsuit.

Well played, Deb.

Well played.

There were lingering signs of my trauma from Ricks. One coworker kept changing the radio from inoffensive soft rock to full-blown twangy country. I would passive-aggressively change it back. One day I was so busy I had to listen to that torture for hours before I could get to the radio—at which point I very aggressively ripped it off the shelf and threw it out the back door.

Eye twitching perfectly on beat to Achy Breaky Heart.

Eventually, summer ended. And it was time.

Since I hadn’t found my eternal companion yet, I was going to have to move up to the big leagues.

I started my first semester at BYU.

And, as before, my education was mostly theoretical. And theological. Against my will, I was there to find a man—not a career path.

Ricks was the junior college to the adult Brigham Young University. Ricks was cheaper. Easier to get into. Friendlier. And yes, I had been accepted to—and offered scholarships from—every school I applied to out of high school. I probably would have gotten into BYU two years earlier if I’d bothered to apply.

But I didn’t want to.

If Ricks was a Mormon school, BYU was a Stick-Up-the-Ass Mormon school.

I was willing to skirt the edges of campus for swing dances. I would even brave the BYU Creamery for their excellent ice cream. But attending school there? No.

I had inherited beef.

My dad was supposed to go to BYU in the 1970s—which never made sense, as he was and remains aggressively Mormon in name only. Back before online registration, students had to physically go to campus with a packet of cards, stand in endless lines at department tables, and grab whatever class slots were left. It could take days.

Dad finally got everything he needed. He was walking out—victorious—when some random hall monitor of righteousness confiscated his packet and told him he could have it back once he got a haircut.

Apparently, his hair was brushing his collar.

Which made him unworthy to attend school there.

Please ignore the statue of Brigham Young as you’re escorted off campus.

Dad never went back. Not to BYU. Not to any other school. He just got a job instead.

So yes. I already disliked BYU.

The people there were so holier-than-thou—and coming from me, that should tell you something. At Ricks, sure, it hit negative sixteen degrees, but people smiled. You talked to strangers. You occasionally got tossed into the air by an overenthusiastic swing dancer. There was warmth. Chaos. Joy.

At BYU? No eye contact. No friendliness. Just a lot of serious don’t talk to me energy.

Also, BYU didn’t feel as safe. On the south end of campus was an area literally nicknamed “Rape Hill.”

Yes. That is exactly what it sounds like.

We were told to avoid it at night. Sir, yes sir. Don’t have to tell me twice.

But they did allow capris on campus, which Ricks did not. So. Growth.

I set aside my anger issues, because BYU was the next best place to meet quality, certified, Grade-A meat—I mean, temple-worthy men.

I changed my major to English. Still a terrible career choice, according to everyone—but it expanded my dating pool beyond theater guys, who never seemed particularly interested in dating women. In hindsight, many of them were probably gay, deeply repressed, and praying very hard about it.

As a Mormon school, BYU had a religion requirement—and absurdly, some of my religion credits didn’t transfer from Ricks.

Explain that to me slowly.

So I had to take extra religion classes to catch up.

So. Much. God.

As an English major, I quickly learned that I hate the English language. It’s a lawless dumpster fire masquerading as a system. The rules are suggestions, the exceptions are mandatory, and pronunciation was apparently decided by a committee of drunk medieval villagers. Through thorough study, you can present the present argument that English exists purely to humble anyone who thinks they’re smart. We spell words one way, say them another, and then act surprised when no one learns it correctly. Don’t even get me started on “colonel,” silent letters, or why “read” refuses to pick a tense and commit.

But I also discovered I loved editing.

We’d write a paper. Revise it. Revise it again. Then swap with a classmate and mark each other’s work. I hated getting mine back with no real feedback. Meanwhile, I returned theirs dripping in red ink—circles, arrows, notes, borderline hostility.

I watched a couple of people nearly cry.

They ended up with better papers. Which was the point.

I loved being a red-pen-wielding tyrant.

I briefly imagined a career in editing, before remembering I was supposed to be a mommy—and also that I would probably be murdered by an angry writer if things continued at that pace.

By the end of my first year at BYU, I realized something alarming.

I was twenty-one.

And I hadn’t really been dating.

Oops.

I had been writing a couple of missionaries.

Missionaries, for context, live under an aggressively detailed rulebook. Constant companionship. No dating. No touching. No movies, no TV, no newspapers, no fun. Limited communication. Approved clothing. Approved music. Approved thoughts. Name tags at all times. You work all day, every day, except Tuesday mornings—when you do laundry, buy groceries, and write letters like it’s 1847.

Young women were encouraged to write male missionaries to support them. Letters were supposed to be wholesome encouragement. Spiritual cheerleading. A morale boost.

Naturally, this occasionally went sideways.

I was writing Grant, a guy I knew in high school, serving in the Philippines. He sent long, thoughtful letters with beautiful handwriting throughout his entire two-year mission. He even invited me to join his family’s Christmas phone call, which his mother was none too pleased about. I thought maybe—maybe—he liked me. He was the first person to give me “Kiss me, you fool” in another language.

Then he got home and never spoke to me again.

Well—no. I did see him in IKEA a few months ago. He and his wife said “hi.”

And I was writing Reed, now serving in London. We exchanged letters and tapes—rambling, flirtatious, wildly inappropriate for missionaries. Perfectly acceptable for junior-high kids. I couldn’t tell if he actually liked me or if I was just a really entertaining pen pal. I probably should have asked outright, but I was afraid he’d say no…or yes—and either option felt dangerous.

I couldn’t take flirting at face value. I had learned to use flirting as a way to survive conversations—be absurd enough and no one can reject you, only the joke.

By the way, you look gorgeous. Rawwwrr.

If Reed was serious, I worried I was distracting him from saving souls and should probably stop writing.

Either way, I stayed safely confused.

If I ever went to a therapist, they would have had several unflattering names for this strategy: avoidance, deflection, intimacy issues with a side of jazz hands.

Either way, in Mormon years, I was officially a spinster. A tragedy. Practically a crone.

So I did the only socially acceptable thing.

I decided to serve a mission.

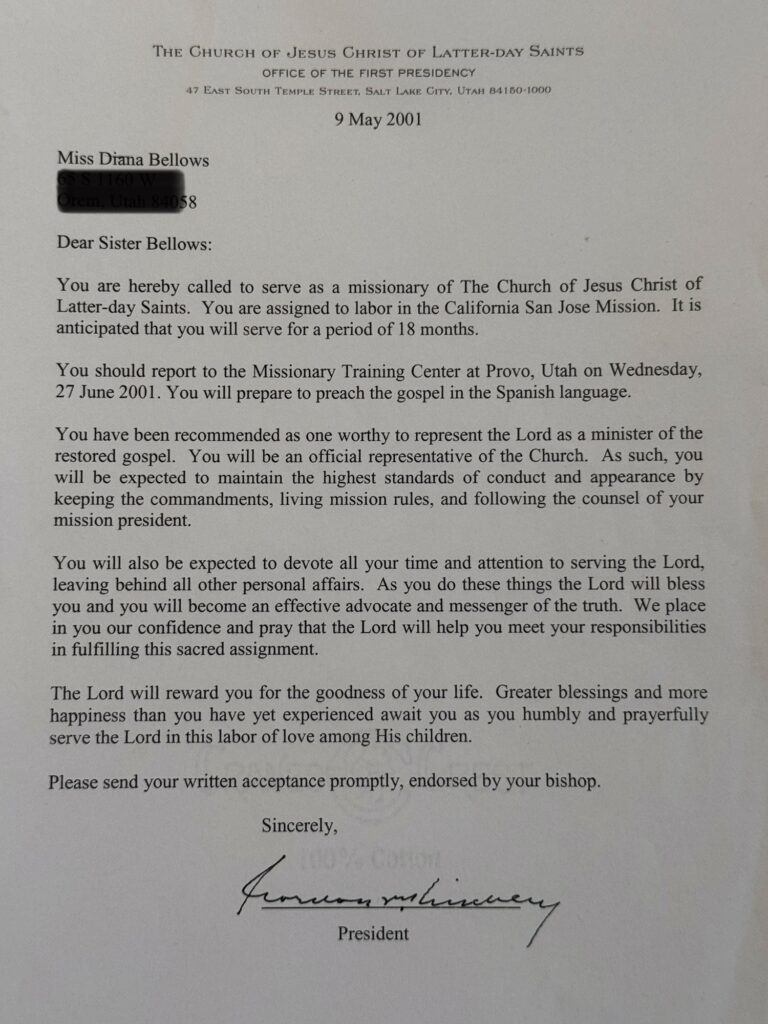

Enlisting was shockingly easy. School ended. I filled out paperwork. Talked to my bishop. Two weeks later, my mission call arrived.

Some families throw parties to open mission calls. Cake. Relatives. Applause.

I sat in the basement with Mom.

I opened the envelope.

There was an unwritten ranking system everyone pretended didn’t exist but absolutely did. A silent hierarchy: foreign and mysterious missions at the top… and then everything else tumbling downhill like a dehydrated pioneer reenactor.

But wherever you were sent, it was the Lord’s will.

I scanned down the page to the big reveal:

San Jose, California. Spanish-speaking.

Mom was relieved I wasn’t leaving the country.

I had to look it up in the atlas. There it was—south of glamorous San Francisco, north of beachy Santa Cruz—wedged like a forgotten middle child. A city of suburban sprawl, chain restaurants, and stucco apartment buildings the exact color of wet Cheerios.

I had never been less excited to go anywhere in my life.

I practiced saying it confidently, like it was the crown jewel of the Lord’s vineyard.

Every conversation went the same way.

“San Jose… Puerto Rico?”

“No. California.”

And then their smile would collapse. Not dramatically—just a soft, visible sag. A tiny moment of pity, like I’d drawn the short celestial straw.

Stupid San Jose.

But there wasn’t time to dwell. I was reporting to the Missionary Training Center in just a few weeks—ready or not.

Mostly not.

Leave a Reply