One of the problems in writing out forty-five years of embarrassment is not knowing where to start. If I immediately dive into the good stories, you’ll have no motivation to keep going. No, no—you don’t get the pizza party orgy story on page one. You have to earn that.

And I don’t need to unload the full scrapbook of my childhood either. We’ll sprinkle those memories in where appropriate, like emotional paprika. What we need right now is a quick montage—a fast-forward through the early years.

So. Childhood.

I was a smart kid. Maybe a weird kid. Probably a normal kid, if I ever admitted that out loud (I won’t).

I never had a lot of friends. I had my brothers and a couple of cousins, and that was good enough for me. The neighbor kids didn’t like us because we were “inactive” in the church. And at school I’d alienated a fair number of classmates by earning the nickname “the kissing girl.”

No, I wasn’t kissing anyone. No, I wasn’t a tiny harlot corrupting the playground. I got the name because whenever the boys would come over to harass the girls on the monkey bars, I’d chase them away making exaggerated kissing noises—like if I caught them, I’d actually plant one on them and give them cooties for life. It worked! The boys fled in terror. Unfortunately, the girls also decided I was some kind of kindergarten floozy and avoided me too.

I spent a lot of time around adults. Specifically, the ladies held hostage in my Grandma’s beauty shop. My mom worked there, so if I wasn’t in school, I was often there too, torturing women whose wet hair and curlers prevented escape. While they sat under the dryers, I would perform for them—singing, dancing, reciting memorized poems like a side show act they never purchased tickets for. Sometimes they’d reward me with a shiny quarter. “That’s very nice honey, here. Now go away.”

During summer breaks, Mom occasionally granted the ladies a reprieve and sent me to the auto shop with Dad instead. I’d follow him around like a very enthusiastic puppy, watching him pull parts and diagnose engine problems after listening to a car run for ten seconds. Ten seconds. To this day, I barely understand the puzzle of auto mechanics, but watching him solve them felt like witnessing sorcery.

Dad is a car guy. He can spot a car from a mile away and tell you the make, the model, and year and whether it was manufactured early or late in the year based solely on the shape of the blinker light. I didn’t care that much about cars, but I cared about him being magic, so I loved it.

Sometimes, when boredom won, I’d wander next door to Grandma Rawlings’ house. There was no performing at THAT Grandma’s. That woman did not applaud. She assigned. Dishes to wash. Raspberries to pick. Walnuts to gather. And no shiny quarter at the end. You just helped.

At school, I was a certified smarty-pants. In fifth grade, they put me in a “gifted program” and I was transferred to another school—which I later learned I only got into because another kid turned it down. I was just on the edge of being considered good enough—a precarious spot I’ve been nervously clinging to ever since. And yet another missing warning label in my life: “Caution: Early academic bloom may wither by adulthood. Side effects of entering into a ‘gifted program’ may include: crushing perfectionism, chronic overachievement, and the haunting suspicion that your best work happened at age eleven.”

I grew up surrounded by expectations—how life should go, who I should be, what I should accomplish. And because I was a rule-follower by temperament and by training, I treated those expectations like they were printed in the instruction manual of my existence. If there was a “right way” to do something, I was going to find it, highlight it, label it, color-code it, laminate it, and follow it to the letter.

It might be because I played too many board games. I was used to rules—clear steps from “Start” to “Finish.” What I didn’t realize until much later is that I learned those games from my brothers, who routinely threw out the real instructions and made up their own as we went.

Maybe that’s why I accepted early on that rules didn’t always make sense and somehow always favored the other players.

But rules were rules. What are you gonna do?

For reasons still unknown, I believed everyone expected me to be a straight-A student. So I became one. I paid attention in class, made friends with teachers, and turned in every assignment on time. I had full meltdowns if I got less than a 98% on a test.

Years later, I mentioned to my mom how stressful it had been to always get perfect grades, and she actually laughed.

“I never expected you to,” she said. “B’s and C’s would’ve been fine.”

FINE?

That’s not fine.

That’s practically failing.

So… maybe it isn’t anyone else’s fault that I turned into an obsessive know-it-all with perfectionist tendencies and a rule-following compulsion that borders on insanity.

That’s fine.

Totally fine.

I’m fine.

So, when I discovered there was a gaping, canyon-sized hole in the knowledge everyone around me seemed to possess about that all-important thing called MORMONISM, I was horrified.

I had never been much of a churchgoer, so when I got to junior high and saw “Seminary” on the class sign-up sheet—an entire class period spent off-campus in a church building specifically for daily spiritual indoctrination—I didn’t think twice. I just… didn’t check the box.

This turned out to be a massive mistake.

Almost overnight, I became a social pariah. No one would talk to me. Especially the kids who didn’t live in my neighborhood and didn’t know my family’s half-in, half-out situation—they didn’t need details. They could smell it on me. I wasn’t a “good” Mormon girl. I was unworthy. Untouchable. To be avoided. Shunned.

After one semester of being invisible—in the bad way, not the cool superhero way—I caved and signed up for Seminary.

And this, ladies and gentlemen, was the pivotal decision.

The butterfly-wing flap that would eventually create a decades-long hurricane in my life.

The moment where my life took a hard left turn into the Book of Mormon Twilight Zone.

I had absolutely no idea what was going on. They kept talking about “Knee Fights,” which sounded like some kind of rough housing my brothers would get in trouble for. I eventually figured out they meant “Nephites.” After that, I learned these Nephites were supposedly ancient Americans descended from transplanted Israelites. And none of this aligned with anything I had ever been taught in actual history classes.

As a good student, this discrepancy alarmed me. How had I missed an entire civilization? Spoiler: I hadn’t. It was made up. But I didn’t know that yet.

I threw myself into catching up—extra reading, extra assignments, extra workbook pages provided by a teacher who was equal parts concerned and delighted, like he’d discovered a stray kitten that could be taught to pray.

And once I was officially inside the system?

I had friends. Lots of friends. Kids my age. That weren’t my brothers or cousins. It was crazy.

And the more I learned, the more praise I got from adults. The more I went to church, the more accepted I was. I studied, I read, I participated in everything they dangled in front of me. I kept going to Seminary. I started going to church every week. I went to Girls Camp (once; hated it). I went to stake dances that required a bishop’s recommendation to enjoy.

Well—if you were modest enough to be let in.

One time, I was turned away at the door because I had bought a pair of “culottes,” which looked like a skirt but were secretly shorts—a modesty innovation, in my opinion. More coverage! No accidental underwear flash when you fell! Peak chastity engineering! But no. Apparently, it was too scandalous to admit to having legs and I was sent home. So, for the next dance, I wore a suitably conservative Old Lady Dress™.

By sixteen, I was fully IN the Mormon cult.

That’s when my mother decided to join me—she even gave up her morning coffee (a beverage not permitted in celestial realms). Every Sunday, we dressed up and sat side-by-side in the pews like a mother-daughter toothpaste commercial for righteousness.

And then, in a twist no one asked for, I was called as a Relief Society teacher.

Me.

A teenage girl.

Standing in front of an entire room of full-grown Mormon women—some my mother’s age, some older—all deeply committed to the system they were now praising me for upholding.

They showered me with compliments. I felt seen. Important. Safe. Like: Ah yes. This is where I belong. I was finally doing it “right.”

Meanwhile, my dad and brothers were still not righteous members, choosing to refrain from church attendance—a fact that caused me to cry into my pillow more than once after a Sunday School lesson about the necessity of having a righteous Priesthood holder presiding in the home. The men in my family were miraculously patient with me during this phase. They never pointed out my superiority complex, never said, “Diana, sweetheart, this is a cult,” never once called out the (now) obvious farce of the whole operation. Saints, truly.

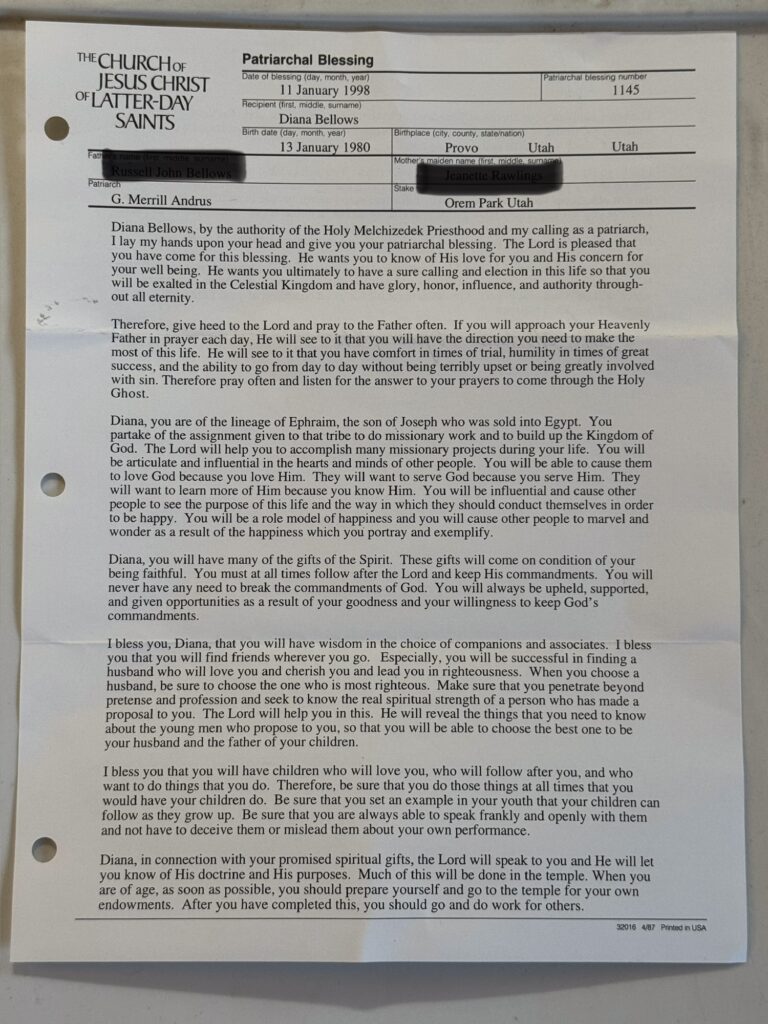

Somewhere during this time I received my Patriarchal Blessing—Mormonism’s very own sacred, “inspired,” palm-reading-adjacent message “from God,” delivered by the guy assigned to be the neighborhood spiritual fortune-teller. It was supposed to offer personal counsel, promises, and direction for my life. Personal scripture. Deeply meaningful.

I don’t remember much of it, except one crucial detail: it informed me that I would find happiness in marriage and raising children.

And I remember thinking: Really? That’s it? That’s all You’ve got for me?

Honestly, I was a little disappointed God didn’t know my heart better than that.

But since the Almighty seemed determined that I fulfill my role as a premium, limited-edition incubator, I continued trying to balance my desire to learn literally everything, with my moral obligation to squash any ambition that extended beyond birthing snotty-nosed babies.

Despite this, I ended up in a lot of Honors classes, but not a single AP class—because no one had ever told me what an AP class was. When I eventually learned that they were basically free college credits (and learned this after it was far too late to sign up), I was annoyed. Briefly. But then I reminded myself: God said my destiny was diapers. So… yay.

I was in an Honors-level Geology class, and since I was at the top of the class, my teacher invited me to tag along on the AP Geology field trip. I happily accepted. My friend Ashley was in the AP class, and her mother had volunteered as a chaperone—so while everyone else was sweating it out in the hot, noisy school bus, I luxuriated in the backseat of a car, caravaning behind them like royalty.

True, I had to endure six hours of her mom’s enthusiastic multi-level-marketing sermon on essential oils, but the legroom alone made it worth it.

What I didn’t realize, because I had gotten approximately zero details, was that the trip involved camping. Thankfully, the tent Ashley’s mom brought was more than big enough for me too.

The trip itself was incredible—three days of geological wonders. Landslide sites, extinct volcanoes, the Grand Canyon. Mr. Clark pointed at rocks like he was introducing us to celebrities. And we “ooo”ed and “aww”ed appropriately, like the bunch of nerds we were.

On the second night, we stayed at Coral Pink Sand Dunes. We sprinted around like hyperactive meerkats until it got dark and cold, then regrouped at the bus where a hot meal and hot cocoa were waiting.

The next morning, some kids felt a little sick, but we pressed on toward Zion. A few miles down the road, the bus pulled over and two kids sprinted into a gas station bathroom. A few miles after that—another stop, another mad dash. Again. And again. And again.

It didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to piece together that something was terribly wrong.

Then my stomach cramped. Hard. And I realized I had not escaped the plague.

At the next stop, I bolted from the car, blessed by the fact that I didn’t have to fight a mob of queasy teenagers. I made it into the single-stall restroom just in time for my bowels to release themselves in a sudden, liquid splash that—thank every deity in the pantheon—landed in the toilet.

I cleaned myself up with shaking hands while fists pounded on the door, and when I emerged, two kids shoved past me—one yanking down her pants, the other vomiting into the sink.

Outside I found a line of pale, sweating, doubled-over high schoolers, waiting like they were in line for the world’s worst amusement park ride.

That stop took a while. A long while.

As the last kids shuffled back to the bus, Mr. Clark came to inform Ashley’s mom that he was cutting Zion from the itinerary. We’d take the freeway straight home instead.

But no.

No, we would not.

We had to take the back roads—the ones with frequent bathrooms.

And so, for the next 250 miles, we slowly crept from St. George to Orem, destroying every available toilet along the way.

That school bus—my God. The stench. The sounds. The puddles. I refuse to imagine it. I have war flashbacks and I wasn’t even ON the bus.

It was later determined that the water in the old metal water tank used to make our hot cocoa had given us all a lovely dose of lead poisoning.

My high school years weren’t all that shitty, though. Statistically, yes, there was a spike during the Great Lead Cocoa Incident of ’97, but overall? Pretty decent.

I found my people—the drama kids. Loud, goofy, quick to laugh, and utterly unhinged in all the best ways. I loved them. I was terrible at acting—spectacularly terrible. I could not emote on command to save my life. But I could memorize my lines, and everyone else’s lines, faster than a TI-84 dying on exam day. I projected like a foghorn and had zero dignity to lose, so I got cast in a lot of shows.

And then there was Megan. Sweet, hilarious, magic Megan—a grade below me, but eons ahead in charm and mischief. I’m convinced we were soulmates in a strictly G-rated, roller-rink-hand-holding way. I once confessed, very earnestly, that I thought I had a cute butt. She laughed like I’d just delivered the greatest punchline in Western literature. I adored her. I adored her entire family—actors, crafters, singers, dancers, and nerdier than a LAN party in a basement full of Magic: The Gathering cards. I didn’t know it was possible to be out-nerded. It was humbling.

Some of my classes were fascinating. Some were so dumb I lost IQ points just by walking into the room. I did well in all of them—except Algebra. Oh, Algebra. My personal Bermuda Triangle.

That first semester I cried every single time I sat down to do my homework. I was obtuse. I was getting Bs—which, to me, was the academic equivalent of being on life-support. I begged my dad to help me. Surely he knew Algebra! He went to college! …for a couple semesters!

He did not know Algebra.

I yelled at him. I yelled at my father. Even I was shocked. But I was drowning in variables and he didn’t punish me—probably because he could see I was one quadratic equation away from a full mental break.

Then, one day, miracle of miracles: we had a substitute. I wish I remembered what she said—some simple little explanation, tossed out like, “Of course this means X.” And suddenly—OH. THAT’S HOW THAT WORKS?!

Suddenly, everything snapped into place. From that moment on, it was 100% on every test. I went from sobbing over worksheets to tutoring my older cousin Teresa and Ashley’s MLM-enthusiast mother through College Algebra.

But when it came time to apply to colleges, I was wildly unprepared. Why would I prepare? I wasn’t supposed to go to college. I was supposed to get married and start manufacturing children like I was running a small artisanal baby farm. That was the Plan. Capital P.

But I was eighteen, and no one had proposed yet, so… college felt like a reasonable way to pass the time between ovulation cycles.

I chose to go to Ricks College.

Before that moment, I had never heard of Ricks. But all my wholesome Mormon friends were going there, so naturally, like any good lemming, I followed. It was a tiny LDS junior college in Rexburg, Idaho. They offered me a two-year full scholarship, which I interpreted as Heavenly Father Himself allocating sacred funds toward my future spiritual wifedom.

I chose my major very carefully—something I enjoyed, but that posed absolutely zero threat of accidentally turning into a career.

I chose theater.

And when I failed to get a callback for a single audition the entire time I was there? I took that as divine confirmation that theater would never distract me from my destiny of diaper-changing, laundry-folding, and eternal, righteous domesticity.

Leave a Reply