A proper Mormon child gets baptized the moment they turn eight and officially become liable for their sins—which, in my case, included fighting with my older brothers, coveting the neighbor’s Barbie Dream House, and one particularly scandalous crime: washing myself “down there” in the bathtub without a washcloth.

My mother caught me mid-suds and reacted like I’d committed treason against the state. Suddenly, my little hand was Public Enemy No. 1. I was told never—never—to touch myself there. Which, as you might imagine, led to some very creative interpretations of hygiene in the years that followed. Let’s just say there were entire regions of my body that went uncharted longer than the Pacific.

But we weren’t a “proper” Mormon family. And I wasn’t baptized until I was almost nine. Which was a near scandal.

But religion wasn’t a priority in our home.

Church attendance was a special event—like Olympic years, or Halley’s Comet.

But I wasn’t a total heathen.

I knew a few hymns. I knew the basic prayer recipe—“Dear Heavenly Father,” gratitude salad, vague promises, “name of Jesus Christ amen.” And I definitely knew my role in Heavenly Father’s plan: be pure, be clean, be virtuous, get married young, have babies.” Which also meant no career. No ambitions. No big life. Just babies. And church. And that would make God, and therefore me, happy.

I wasn’t a fan of that plan, and therefore, not a huge fan of the church either.

I remember I was asked, once, to give a talk in Primary (the kids’ level indoctrination class on Sunday) The topic was “My Hero.” I took it very seriously. Wrote a speech. Memorized it. Rehearsed it for my mother while standing on our fireplace mantle.

Come Sunday, I marched up front, wearing the pinkest, froofiest dress in existence, and delivered an enthusiastic five-minute tribute… to Oprah.

I don’t remember the adults’ reactions, but retroactively, I assume there was fainting. Maybe a small stroke. This was Orem, Utah in the mid-80s—land of white middle-class patriarchal uniformity. These people were expecting Spencer W. Kimball. Joseph Smith. At minimum, Jesus. Instead, they got me, reporting live from the Church of Daytime Television. If I’d come with a warning label, it would’ve said: May Contain Traces of Feminism.

So, it should shock absolutely no one that when my baptism finally arrived, I had no idea what was actually supposed to happen. I knew I’d get a new dress—a fondness for which I have had my entire life—and that extended family would show up and pretend I suddenly mattered for forty-five minutes. Cake, attention, new outfit? Absolutely. Dunk me, Daddy.

I zipped up my white jumpsuit and walked towards my fate. After the dunk I emerged from the font feeling like a triumphant, slightly bewildered otter. They handed me a towel and sent me to the locker room.

I waited for divine electricity. A warm spiritual buzz. Something. Anything.

Nothing. Even though I had clearly just gotten thoroughly damp in front of a small audience.

Maybe that Jesus Jacuzzi was broken.

So, I started getting dressed.

It did not occur to me—nor apparently to the adults supervising this sacred rite—that I might need a change of underwear. A detail so vital, so obvious, so crucial to human comfort, you’d think someone would have mentioned it. But no.

And truly? That moment was a preview of how much of my life would be for me: No instructions, no warning labels, and me standing there in something wet, wondering, “Is this… normal?”

If you don’t know me, let’s set the stage—because context, darling, is everything, and I refuse to have you wandering into this story cold like you accidentally switched channels.

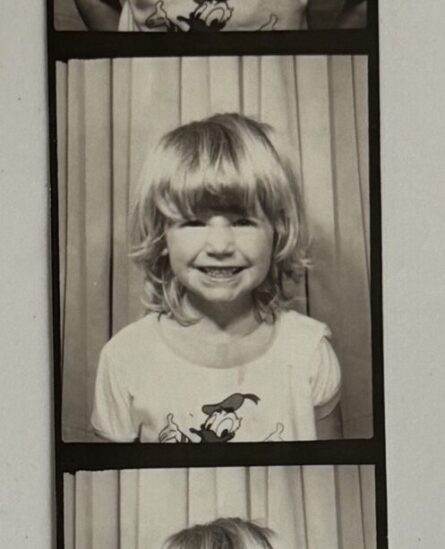

I arrived on the scene in January 1980, the third child of two sweet, quiet, conservative parents who considered mild disagreement the equivalent of full‑scale rebellion.

Right out of high school, my mother began working in my future grandma Leona’s beauty shop—which was in her basement, naturally—two sinks, two chairs, and a battalion of hood dryers in turquoise blue. Every surface was lacquered in a fine mist of hairspray.

My dad went to work for his father‑in‑law in a scrap yard: a couple of acres of cars in various stages of decomposition. The shop smelled like gasoline, paint, and pure American nostalgia. In other words: heaven.

They married young, bought a yellow house on a corner lot, located between both sets of parents—geographically efficient—and they still live there to this day.

I have two older brothers, Jason and Alan, and as the youngest and the only girl, I was spoiled rotten in a way I highly recommend. We played outside in a neighborhood where everyone knew everyone’s business. We roamed feral until the streetlights flipped on or until Dad’s whistle cut through the air.

We watched only edited‑for‑TV movies, and even then, my mother kept a dishtowel poised like a moral ninja to slap over the screen if a kiss lasted longer than two Mississippis. We were sheltered. If innocence had a ZIP code, we were its premiere residents.

Now, as for me: I’m Diana.

If you saw me walking down the street, you’d hear me first—my laugh is loud enough to be heard over the roar of a motorcycle engine (it’s been verified)—then you’d see me: short, blond, a little chubby, pale enough to reflect moonlight, freckles for seasoning, a Roman nose, narrow lips framing a giant grin, and a complete absence of poker face. I am emotionally transparent to the point of being a security risk.

And though they do change during the course of this narrative – as do so many things – you should know about the boobs.

H-cups. Thirty-four H. Yes, that’s a real bra size. Imagine two overzealous cantaloupes duct-taped to a soda can. They got attention. Way too much attention. I tried to hide them, bind them, contain them—but those girls were like inflatable tube men outside a used car lot:

“HEY, YOU! YES, YOU! SAY SOMETHING INAPPROPRIATE! NO, REALLY, DON’T HOLD BACK!”

And, of course, I came by these honestly. My father’s sister—our infamous “Pretty Auntie Norma”—was mythically endowed. A Double K, practically a local landmark. At her funeral, I learned that in 1960s San Francisco, she embraced the bra-free lifestyle, and got wedged in a revolving door, jamming the mechanism, which required the fire department to dismantle the whole thing. A job which probably took them longer to accomplish than strictly necessary, because they were all doubled over laughing.

I am still offended I didn’t hear this until after her death. In my family, embarrassing stories are communal property. We gather around the kitchen table and retell them until our sides ache, tears stream, and someone hopefully starts laughing so hard they go hypersonic. No shame. No secrets. Just shared mortification. It’s not just entertainment—it’s our family’s official love language.

So, if you’re ever unsure while reading these stories, assume they’re meant to amuse. Embarrassment is just the toll you pay for a good punchline. A few tales wander into darker terrain—but don’t worry. I make it out alive. Mostly. My dignity survives with minor bruising.

And yes—if you do know me, I’m sorry. You may be a character in here. You may already be sick of these stories. Too late now.

And if you are my mother: STOP READING. IMMEDIATELY.

And that’s the stage set. Welcome, darling.

Here’s my trauma.

Please enjoy responsibly.

Leave a Reply